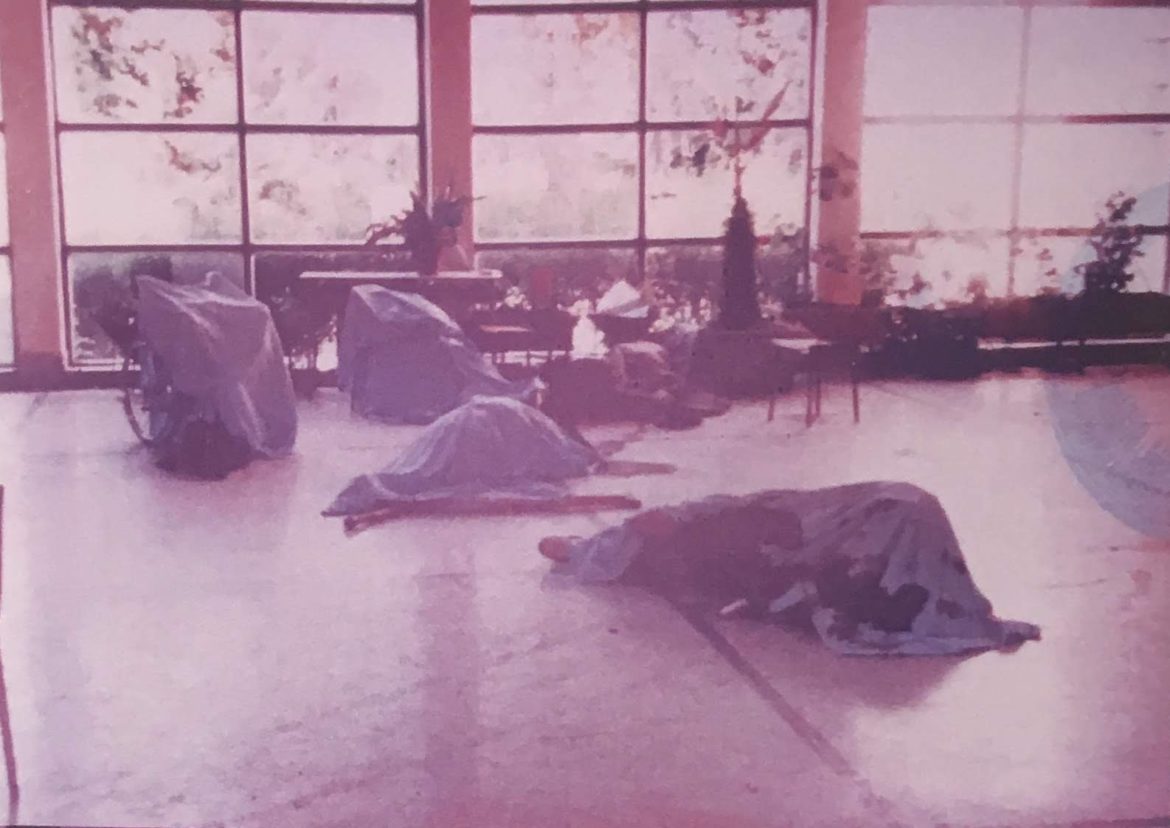

Dead bodies in the school hall covered with blankets. Photo from Danish State Attorney.

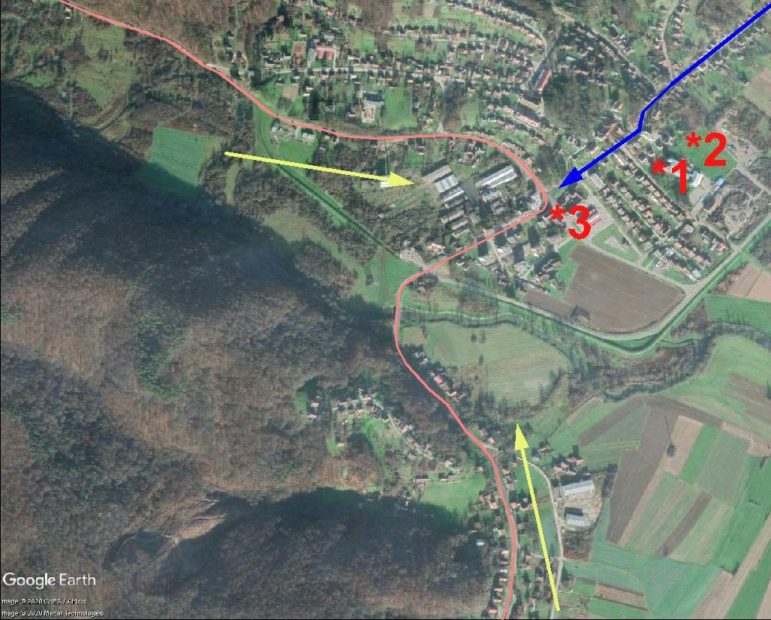

“I observed a group of about 12 soldiers arriving on foot along the road. I could not identify to which party they belonged. They were wearing either camouflage uniforms or one colored khaki uniform. Some wore hats or caps but I can not give more specific description. They took position lying behind the wall along the road and facing the school. Three soldiers went forward and took positions lying on the lawn situated between the road and the school. Shortly after two or three soldiers approached the school. They disappeared behind the building.”

“Then one of the soldiers from on the lawn went to the school and looked through the windows. He signaled to the soldiers behind the wall and they started shooting. Immediately after shooting could be heard from inside the school”

The school in the background as it looks today. The killers lied down on the lawn behind the small wall – looking into the school. They used the small path on the picture to get to the back entrance of the school. Photo: Jerko Bakotin.

August 8, 2020, marked 25 years since Christian Jensen witnessed this incident — a description of which he gave a few days later to Danish investigators. The investigators sent their findings to the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia, ICTY.

At the time, Jensen was a 54-year-old senior sergeant with the Danish battalion of the United Nations mission in Croatia. The battalion was based on two playing field – one of them only 5-10 meters from the school building in the town of Dvor in the Banija region.

The area had been part of the territory held by the secessionist Republic of Serbian Krajina, an unrecognised entity established by rebel Croatian Serbs within Croatia in 1991 as Yugoslavia collapsed.

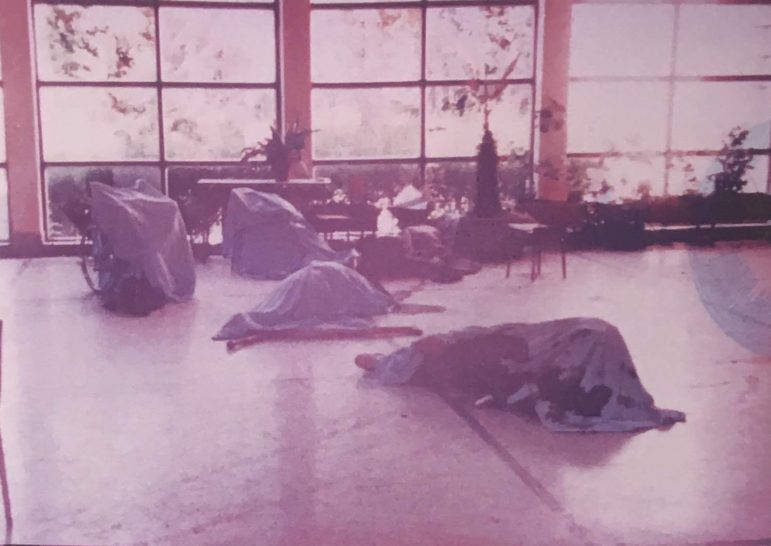

In early August 1995, the Republic of Serbian Krajina disintegrated during Operation Storm, a military offensive by vastly superior Croatian forces to take back territory held by the rebels, aided by a rear attack by the Bosniak-led Bosnian Army’s Fifth Corps.

Some 200,000 Serbs fled Croatia as a result, many in a long convoy of cars, buses and other vehicles that headed along the road that led through Dvor and then across the border to Serb-controlled territory in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Residents saved in an elementary school

This photo shows the back entrance through which the killers entered the school – see the small door at the right side. Photo taken in 2020 by Jerko Bakotin.

Among the fleeing Serbs were around 50 residents of a psychiatric hospital and a retirement home in the town of Petrinja. They were evacuated to Dvor and given shelter in the town’s elementary school, three kilometers from a bridge over the River Una, which led to relative safety across the border in the Bosnian town of Bosanski Novi, since renamed Novi Grad.

By August 7, most of the people who were at the school had managed to leave. They either phoned relatives to pick them up, joined the refugee column or walked over the bridge. But around 10 of them stayed – those who were unable to leave without anyone to help them. Most were Serbs, but at least one Croatian woman was among them. Some had serious mental or physical disabilities.

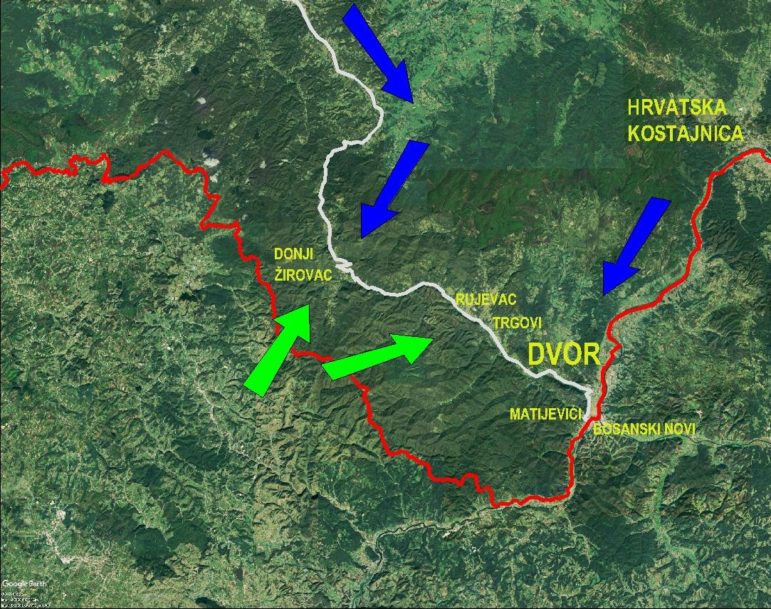

Croatian soldiers pushed into Dvor in the late afternoon of August 7 and intercepted the convoy of refugee vehicles at the traffic circle near the bus station. A firefight ensued with Serb soldiers from the convoy, and both sides incurred losses.

Civilians were killed as well, some allegedly after surrendering to the Croatian Army, as brothers Vlado and Nikola Saso claim happened to their parents.

For the Serbs, it was crucial to hold the crossroads in order to secure the road from the Croatian town of Glina to Bosanski Novi, which was the escape route for tens of thousands of Croatian Serbs from Kordun and Banija regions.

The Wider Banija region in “Operation Storm”: White line – Glina-Dvor road. Red line – the border to Bosnia. Green arrows – 5th Corps attacks. Blue arrows – Croatian attacks. Dvor ended being the last town before crossing Una river and fleeing to Bosnia for the Serbian army and civilians.

Next morning, the remnants of the Republic of Serbian Krajina Army counterattacked from the west and south in order to allow the refugee convoy to proceed, and Croatian troops withdrew to positions just outside the town. More precisely, Croatian Army retreated to the crossroad where Kostajnica-Dvor road bisects into the main road heading to the Dvor’s town center and the southern bypass road.

The Croatian and Serb versions of these events mostly coincide up to this point. But there is disagreement about who controlled the area around the school in the early afternoon of August 8 – and on whose side the soldiers were who approached the school around 2:50 p.m. that day, “lurking”, as one Danish soldier said, “as if they were doing something wrong”.

The mysterious unit entered the school

Dvor on August 7th and August 8th early morning: Rose line – movement of Serb refugee column. Blue arrow – Croatian push into Dvor on August 7th evening. Yellow arrows – Serb counterattack next morning. 1 – School. 2 – UN Base. 3 – Traffic circle. The Serbian counterattack and taking the city back happened August 8th before a Croatian unit tried to fight back.

“Two of the soldiers went upstairs, and the two others went into some of the rooms on the ground floor. Twice I heard the sound of shooting, three to five rounds each time,” Jan Wellendorf, a senior sergeant with the Danish battalion of the United Nations mission who had a direct view of the school hall, told the ICTY investigators.

The soldiers then lined up the refugees in the entrance hall, including wheelchair-bound Zorka Maric and 80-year-old Desanka Teodorovic, who was on crutches.

All the Danish witnesses point to the fact that at this moment the soldiers have taken out several refugees from the school and forced them to walk away, with their hands behind their neck. Christian Jensen described one of these persons as a “captive soldier”, wearing khaki-coloured trousers and boots.

The remaining two soldiers stood in the center of the hall.

“Suddenly one soldier fired three to four rounds at the old woman. I saw her collapsing in the chair. The same soldier shot single rounds against the other civilians. They fell on the floor. It was obvious they were dead,” continued Wellendorff.

The view of Wellendorff in 1995 – into the school hall. Photo by the Danish State Attorney.

The view into the school from the position of Wellendorff. Photo taken in 2020 by Jerko Bakotin.

Wellendorff was placed on an observation post with direct view to the schools aula, while Jensen was manning an observation post that made it possible to overlook the side of the school building facing the road.

“Soon after the remaining soldiers in the group left along the road and were not seen again,” he said.

Only a couple of victims DNA identified – disagreements of number of deaths

The massacre at the school was reported by the New York Times on August 10. In the weeks that followed, Danish investigators working for the ICTY questioned a number of witnesses, whose testimonies Investigative Reporting Denmark, IRD, has acquired from the Danish Military Command.

However, 25 years later, the perpetrators of the attack in the school in Dvor remain unidentified and unpunished, and Serbia and Croatia continue to blame each other for the killings.

Not only does the identity of the perpetrators remain unknown but most of the victims remain unidentified today as well.

Only a couple of victims were identified through DNA analysis and given a proper funeral, the rest still being buried in a collective grave.

Even the number of the executed is unclear. According to the UN documents, nine people were massacred in the school – six in the entrance hall, and three in the classrooms on the ground floor and first floor.

However, the Croatian police report dated August 13 documented 12 bodies. Ten are found in or close to the school. Two additional bodies, brought in the vicinity of the school, belong to an identified Croatian local couple. Their murder is often taken together with the school massacre as one case.

Danish-Croatian journalist team thoroughly researched the circumstances of the massacre, talking with more than 40 people, including former soldiers, police investigators, civilians and both official and unofficial sources from various institutions in Croatia, Serbia and Denmark.

A great deal of hitherto publicly unknown information, details and documents surfaced. They shed a new light on the extraordinary complex situation in Dvor on August 8, 1995, a day on which – counting the Danes – at least five different army and paramilitary formations were in Dvor or within a couple of kilometers nearby.

Bosnian Army troops initially suspected

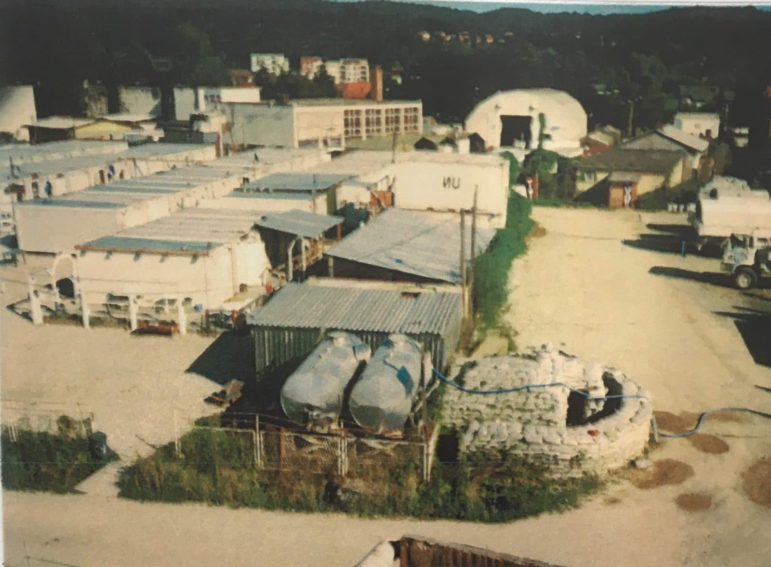

Danish base in Dvor, Croatia, in August 1995 – with the school in the back. Source: Danish State Attorney.

The first reports from the Danish UN troops put the blame for the executions on the Bosnian Army’s Fifth Corps – for several reasons. First, together with the Croatian Army, the Fifth Corps attacked a Serb refugee convoy in the village of Donji Zirovac, around 25 kilometres northwest from Dvor. At least 16 civilians were killed. There were also reports of a Bosnian Army attack on Serb refugees in Trgovi, nine kilometres west of Dvor.

Less than two hours after the massacre in the school, the Danish battalion sent a dispatch raising suspicion that the Fifth Corps was responsible.

Its presence in Dvor was possibly explained as a “revenge for the loss of a Fifth Corps 505th Brigade Commander”, implicating Izet Nanic, who was killed few days ago in the fight with Serb forces.

One reason for attributing the crime in Dvor school to the Bosnian Army was the spotted military insignia.

“One person had a shield on his upper arm, red with two V-like signs at the upper edge,” Christian Jensen said, describing the only one of the killers who had any insignia.

“I thought that the ‘V’ could be Roman numeral 5, for the 5th Corps”, explained Chief Danish commander in Croatia, Colonel Jørn Jensen during joint interrogations of Danish soldiers by the Serbian and Croatian prosecutors in 2012 in Copenhagen, whose content is being reported for the first time by Balkan Insight on August 8th 2020 in a short version of this investigation.

Nevertheless, neither was Colonel Jensen present in Dvor nor the Fifth Corps’ insignia includes the Roman numeral ‘V’. On top of that, while being questioned in 2012, Christian Jensen was shown various Bosnian, Serbian and Croatian insignias, and did not recognize any of them.

Despite the fact that neither Christian Jensen, Jan Wellendorff nor other witnesses could tell if the perpetrators of the Dvor massacre belonged to the Bosnian Army, Republic of Serbian Krajina forces or the Croatian Army, the claim that the Bosnian Army was responsible still made its way into numerous Danish military, UN and media reports.

However, several military commanders – both Croatian and Serb – as well as civilians present in Dvor at the time have confirmed there were no Bosnian soldiers in the wider Dvor area before August 10 or even later, so Fifth Corps troops could not have carried out the killings at the school.

Sources from both the Croatian State Attorney’s Office and the Serbian War Crimes Prosecutor’s Office also told IRD that they have ruled out a Bosnian Army presence in Dvor at the time of the killings. It means that the perpetrators came either from the Croatian or from the Serbian ranks.

Serb counterattack in the morning pushes Croats out of Dvor

In a 2015 Danish documentary about the massacre, Republic of Serbian Krajina Army General Mile Novakovic claimed “the school was of no interest to Serb forces”. However, Investigative Reporting Denmark has now established that on August 8, both Serb and Croatian units were near the building.

“Around 6 a.m. we managed to organise 150 to 200 soldiers. Morale had been shattered, everyone was worried about his family in the refugee convoy. We advanced slowly, as the Croatian Army opened fierce fire towards our positions. Around noon, my group pushed into the center of Dvor,” the chief of staff of the Republic of Serbian Krajina Army’s 13th Brigade, Colonel Lazo Pekec, told IRD.

Colonel Pekec entered Dvor from the west, and was involved in ensuring the safe passage of the refugee convoy until 10 p.m. that evening.

Another Krajina Army officer confirmed that on the morning of August 8, they “ejected the Croats from Dvor” and met Novakovic’s forces, who attacked from the south.

Novakovic himself wrote that after re-entering Dvor, he deployed a Banja Luka Special Police detachment in the town center, meaning that it could be argued that the area around the school was under Serb control around the time of the massacre.

Many different fighters in Dvor on the day of the Massacre

However, the situation in Dvor and in the wider conflict area was quite confusing.

“There were many unknown fighters. Every couple of minutes somebody would ask ‘Whose army these soldiers belong to?’ Unknown people, same or similar uniforms, same language – all that creates a chaotic situation,” remarked Pekec years later in the text he wrote on the breakthrough through Dvor.

The Serb forces in Dvor did not consist only of the Krajina Army: in fact, they originated from three different countries. As well as the Krajina Army and the Banja Luka Special Police detachment from Serb Republic in Bosnia, the State Security Service’s Unit for Anti-Terrorist Operations from Serbia was also in the area.

Its members were known as the ‘Red Berets’ and were sometimes described as ‘Arkan’s Men’ by civilians who confused them with the Serbian Volunteer Guard, a paramilitary unit led by Serbian warlord Zeljko ‘Arkan’ Raznatovic. The sources from the Croatian State Attorney’s Office also sometimes described Red Berets fighters as Arkan’s Men.

To further complicate the issue, sometimes the whole squads were transferred from the Red Berets to the Serbian Volunteer Guard and back.

Moreover, both the Red Berets and the Serbian Volunteer Guard had previously assisted troops loyal to Serb-allied Bosniak warlord Fikret Abdic in nearby Velika Kladusa, near the Croatian border, and then escaped from the area during Operation Storm.

Serbian ‘Red Berets’ came under scrutiny

A senior source at the Croatian State Attorney’s Office said that its officials believe that a group made up of Red Berets and Republic of Serbian Krajina soldiers were responsible for the massacre.

The source said that on the morning of August 8, Arkan’s Men were patrolling in Dvor and forcing local Serbs to join the refugee convoy and leave the town. As Dvor was a Serb-majority town, those who chosed to stay were considered traitors.

A Dvor resident told ICTY investigators that on August 8 around 9 a.m., he and his wife first heard shooting which lasted for about half an hour. Then they saw two soldiers coming from the bus terminal close to the mentioned traffic circle.

“They first broke into my neighbours house. Then they ordered us to come in the street with our hands up. They asked who we are. I told them I was a Croat. One of the soldiers ordered me to kneel down. He asked me why I have not joined the column of refugees. I told him I was sick and could not leave. He has taken his knife and put it to my throat but after questioning me he put it back,” said the witness, who IRD was able to identify as Zvonimir Baburak.

His family house is a mere 50 meters away from the school, which is separated from Baburak’s backyard only by the narrow road. With that taken into account, Baburak could be a key witness – and accordingly he gave quite a long statement to the investigators working for the ICTY.

The soldiers sat down and accepted the brandy and coffee that Baburak and his wife offered, he told.

“They seemed to be nervous,” remarked the frightened host.

Baburak said he did not know “what force the soldiers belonged to, they had no insignia”.

The soldiers inquired if there were Muslims in the school, then left for the school building, with three or four other soldiers joining them.

“Later we heard shouts of ‘Come out’ and ‘Surrender’, and shooting at the school. Later I saw soldiers had taken around six civilians from the neighbourhood apartment building. They took them to Bosanski Novi,” said Baburak.

Afterwards he was visited by his brother, accompanied by a soldier from Leskovac in Serbia – his place of origin indicating he could have possibly belonged to Red Berets or to the “Arkan’s Men”, as these were more often composed of fighters from Serbia rather than from the local Serbs. The soldier asked him to identify a corpse lying in the street nearby.

“It was our local barber. Some of his head was missing. Next to him was a dead pig,” said Baburak.

The barber was a local Croat named Nedjeljko Ivelic. His wife had also been killed. Her body was found in Ivelic family house.

Later Baburak also found the corpse of a young man in military trousers lying near the school, his throat cut. In the evening, he went to his brother’s house, also not far from the school, where he said that Serb soldiers – some with “brimmed black hats like cowboy hats” – boasted that there were “10,000 of Arkan’s Men” in the area. One soldier showed Baburak that they had Croatian, Bosnian and Serbian insignias and changed them at will.

Baburak presumed the barber and his wife were killed by “Arkan’s Men” or “Chetniks” – a general term for Serb paramilitaries, often involved in atrocities.

Five Croatian soldiers killed – the sixth got shelter in Danish Camp

The Croatian State Attorney’s Office source said there were numerous accounts of Arkan’s Men being active in Dvor that day.

“We have a witness who was thrown out of her house by Arkan’s Men at noon. Another witness saw that Arkan’s Men beat an Orthodox priest who did not want to join the convoy,” said the source.

The Croatian State Attorney’s Office also believes that Serb fighters killed five Croatian soldiers from 17th Sunja Homeguard Regiment who did not withdraw when the Croatian Army retreated that morning but took shelter in one of the houses across from the school instead.

Between 10 a.m. and noon, they were captured and executed in a cornfield near the bus station. A sixth soldier who separated from the group survived by asking for shelter at the Danish base.

“He said all of his comrades are dead,” Thomas Karstenskov, who was guarding a Croatian soldier, told Investigative Reporting Denmark.

This could possibly mean that the Croatian soldier saw the execution of the aforementioned five Croatian soldiers. Investigative Reporting Denmark knows the soldier’s identity. He declined to talk with the media, however, Croatian State Attorney’s Office interrogated him in 2012.

Traffic circle for the Glina – Bosanski Novi road as it looks today. This traffic circle was important for the Serbs to keep under control to secure the retreat. Photo: Jerko Bakotin.

“We assume that the Ivelic couple, the disabled people in the school and the five Croatian soldiers were killed by members of the same units, including the Red Berets. More than 100 witnesses have been questioned, including Baburak who was interrogated several times, starting with 2012. All the witnesses questioned at the beginning of the investigation said the killers were Arkan’s Men,” told the Croatian State Attorney’s Office source to IRD.

A Danish military log entry dated August 8 also says that “civilians in Dvor have indicated that the liquidations were carried out by Arkan’s Men.”

Croatian State Attorney point on specific Red Berets officer

Although the Croatian State Attorney’s Office source is still trying to identify the direct perpetrators, it believes that there is a greater chance of identifying the units to which they belonged.

“Then it would be possible to indict the commanders according to the command responsibility principle,” the source said.

The source named a specific Red Berets officer as possibly “relevant for solving this crime”. As the Croatian State Attorney’s Office declined to present any proof for this claim, citing the confidentiality of the investigation, Investigative Reporting Denmark decided not to publish the officer’s name.

Nevertheless, IRD did managed to contact him by telephone. The officer said that his unit went through Dvor while retreating from Croatia but insisted that it did not stop there.

“We started our journey from Velika Kladusa on August 5 and barely managed to get out alive. We crossed over into Bosnia immediately. During the whole of the journey we had little contact with the Croats and were mostly fighting with the Bosnian Army’s Fifth Corps,” he said.

“The claim that my soldiers killed people in the school is nonsense. There is no chance of that – it was a very disciplined unit. I came to defend the Serb people, not to kill them,” he added.

It is worthy to remember that Baburak said soldiers in his garden inquired, “if there were Muslims in the school”. It makes sense for a Red Beret to ask that, as they were retreating in front of the Bosniak-led Fifth Corps, while the Croatian Army by this point had no contact with Bosniak troops in the Dvor area.

Several weak points on claiming Serb soldiers responsible

Nevertheless, the claim that Serb soldiers committed the massacre in the school has several weak points.

To start with, it could be argued that the credibility of Baburak’s testimony is questionable. The circumstances of his interrogation are crucial.

Danish investigator Willy Hove questioned Baburak on September 8, 1995, when it was completely clear the Krajina Army was routed from Croatia for good. If he knew the soldiers were Serbs, there was no reason for him to be afraid and not tell that to Hove, who was working for ICTY.

“During the interrogation, the battery on my laptop died. So we went to the Croatian Army Headquarters in Dvor to do the questioning,” said Hove to IRD.

Investigators remembered that there they got a room of their own. However, it was clearly not the best location to do the interview. The Croatian Army committed numerous war crimes during and after Operation Storm. In the Croatian headquarters, Baburak was surely not in a position to speak freely and to possibly accuse Croatian soldiers.

“The witness was quite nervous,” remarked Hove.

It was his impression that Baburak knew more than he said.

Baburak stated earlier “he does not know to which side did the soldiers who came to his house belong”, a claim quite unlikely for someone living in Krajina. The soldiers who threatened Baburak came to his house around 9:30 a.m. Even if they were Serbs – Croats would have been unlikely to sit and drink coffee and brandy in the middle of Serb-controlled Dvor – the massacre happened hours later (2:50 p.m.).

Unfortunately, Baburak died in 2018.

IRD also found a Croat civilian who was forcibly deported by Serb forces to Bosnia on August 8. This seems to confirm Baburak’s and Croatian State Attorney Office’s claims, nevertheless, the witness – who asked to be anonymous – stated he was deported by ordinary soldiers, not Arkan’s Men. In addition, although the deportation was forced upon him, it was done without violence.

The same witness claimed that in the days before August 8, the Republic of Serbian Krajina Army ordered two young soldiers to guard the disabled people at the school.

As mentioned, Christian Jensen described one of the people taken out of the school as a “captive soldier”, and Baburak reported he found the body of a young man in military trousers near the school. It is possible that this could be one of the guards the Serbs assigned to the disabled in the school.

Further questions are raised because during the whole of Operation Storm, there is not a single confirmed instance of Serb soldiers massacring Serb civilians.

It is still possible that Serb units have executed the handicapped people in Dvor in order for the massacre to be attributed to the Croatian Army.

However, the crime happened in the last minute of the war, at the time when the Serb civilians and soldiers alike were running for their lives. It is not very likely that the Red Berets would waste time to kill Serb civilians less than a kilometer away from the Croatian Army positions.

Finally, all the Danish soldiers agree that the killers behaved as if they were attacking an enemy position when approaching the school.

Christian Jensen described the soldiers lying on the ground to protect themselves from potential fire, while Jan Wellendorff and others claimed the school was hit by a shell and a hand grenade. A Serb squad operating in Serb-controlled Dvor would have been unlikely to behave as if it was infiltrating enemy territory or attacking an enemy-controlled building.

Eye-witness Christian Jensen, former senior sergeant with the Danish battalion of the United Nations mission in Croatia, describes the slaugthering as an operation with no military purpose. Only purpose was pure terror. Photo: Private archive.

Croatian Army soldiers also accused

“On August 8 there was no soldier or unit under the command of the Croatian Army in Dvor,” claimed colonel Bruno Cavic of the Croatian Army 145th Brigade in the 2015 Danish documentary about the massacre.

The documentary sparked public fury in Croatia for showing men who were allegedly Croatian soldiers close to the school on that day. A witch hunt lasting months ensued. The powerful war veteran associations forced the head of the Croatian Audiovisual Center, which co-financed the movie, to resign, while journalist Saša Kosanović was fired from the public broadcaster for working as a fixer on the film. The movie itself was never screened in Croatia.

Both Cavic and other Croatian commanders claimed that after withdrawing from Dvor on the morning of August 8, they did not re-enter the town before August 9 – well after the massacre in the school. However, Cavic was in only charge of his own brigade and there were several other Croatian units present.

Croatian Army was in Dvor in the morning of the 8th of August 1995

IRD was able to establish that the Croatian Army actually entered Dvor not twice, but three times. The second time was on the morning of August 8, after the Serb counterattack drove the Croat troops out of the town.

In 2011, Zagreb-based news weekly Novosti translated excerpts from the Danish military log which noted heavy fighting and a wounded Croatian soldier near the school that day.

IRD acquired additional dispatches recording intensive fighting in the center of Dvor in the afternoon of August 8-fighting which was still going on in the evening. Among the documents used in the ICTY trial of General Gotovina, there is a document written at 6 p.m. on August 8 by the Croatian Chief of General Staff Zvonimir Červenko, mentioning that there is an ongoing “energetic attack operation with the goal of complete liberation of Dvor”.

The main Croatian commander in the Dvor area was Zagreb Military District Chief of Staff, Brigadier Vinko Stefanek. He confirmed that Croatian Army briefly re-entered Dvor on the morning of August 8.

“After the fighting the previous night I ordered a withdrawal to the crossroads at the northern edge of the town. In the morning, there were some probing efforts, not organized and very limited,” Stefanek told IRD.

Another officer confirmed that after around 100 meters, Stefanek ordered his forces to halt.

However, according to the IRD’s findings, during “Operation Storm”, the Croatian Army was not perfectly organized, as was usually presented in Croatian public.

Chaotic situation in Dvor thanks to fired commander

Instead, the situation in the Dvor area was almost chaotic thanks to General Ivan Basarac. He was supposed to be in charge of the frontlines in Banija. But after the first day of attack when his troops failed to make real progress, resident Franjo Tudjman fired Basarac from the position of Zagreb Military District commander and named General Petar Stipetic as his successor.

Nevertheless, Basarac continued to appear on the frontlines and made orders on his own although he lacked the authority to do so. The other Croatian commanders wanted to wait for a Serb convoy and army to pass and leave Dvor in order to avoid unnecessary losses on both sides and the killing of civilians as well. However, Basarac insisted on attacking as soon as possible.

Despite Stefanek’s orders, one 17th Sunja Regiment battalion pushed on further, using the southern bypass road which goes by the river, passing the school playing field where the Danish battalion had its base and almost coming all the way to the southern edge of Dvor.

Some Croatian soldiers were indeed captured by the Danes’ cameras. The videos are actually posted on YouTube by a member of the Danish battalion. One camera also filmed the wounded soldier mentioned in the military log. IRD was able to identify the man as Sasa Simic.

Sasa Simic, wounded Croatian soldier, confirms now he was in Dvor in the morning of 8th of August 1995. Photo: Jerko Bakotin.

“I was walking on the other side of the embankment situated by the road. After passing the UN base, I suddenly saw a mass of Serb soldiers. They tried to encircle us, but they could not do it properly because of the UN base. Otherwise, they would wipe us out completely. I threw a grenade and opened fire,” said Simic, speaking to media for the first time.

“Then I felt I was hit. When I regained consciousness, I asked my guys to take me to the UN Camp. The Danes gave me morphine,” he added.

Croatian pushes August 8th morning: Short blue arrow – main Croatian attack, soon stopped on Stefanek’s orders. Long blue arrow – movement of certain Croatian groups on the bypass road. At red point 4 Simic is lying wounded and that is recorded by the cameras, as his comrades brought him to the Danish base to ask for help.

The Danish military log records that this happened shortly before 9:30 A.M. – hours before 2:50 P.M., when the massacre took place. However, according to the direction from which the killers came, it is possible that they arrived from the area that Croatian forces had already reached that morning.

Moreover, Jensen, who was best positioned to observe the road, said that after the shooting, the killers walked away towards the north-west. That direction led to the place where the Croatian troop positions were at the time, less than one kilometer away – and possibly only several hundred meters.

“The attack on the school was a cleansing operation, done very professionally, but with no military purpose. The only purpose was pure terror,” Jensen told IRD.

This description fits the pattern of other crimes committed by Croatian forces during and after Operation Storm.

Killing soldiers did not wore stripes

The route of the murderer squad: Turquoise line – the way the murderers came. Orange line – the way they left. 1 – School. 2 – UN Base. 3 – Observation point of Christian Jensen. 4 – Baburak house. 5 – Line of houses where five Croatian soldiers were captured. According to DORH: They were executed in the corn field near the bus station. 6 – Bus station.

However, Croatian soldiers usually wore colored stripes on their shoulders so they could recognize each other, the exact combination of the colors being changed every two days.

Jan Wellendorff notes that thanks to the stripes, Croats were “very easy to distinguish”.

The perpetrators of the massacre wore no stripes, although they could have removed them.

It is also unclear why a Croatian unit would endanger itself by massacring civilians and attracting attention while the area was still under Serb control.

“It would be unrealistic if the Croats would begin to clear the houses around the school before they controlled that part of the city,” captain Erik Sørensen, another Danish eyewitness, told IRD.

As illogical as this seems, it is still more unreasonable that Serb soldiers would attack a school building in the middle of Serb-controlled Dvor to kill mostly Serb civilians.

It is as well significant that Simic confirmed that the soldiers shown near the school in the Danish movie belong to his unit. As already pointed out, it was hours before the massacre.

However, it shows that the public hysteria in Croatia regarding the movie was not based on the facts – more concretely, that the Croatian commanders did not speak the truth when they stated that there were no Croatian soldiers in Dvor on August 8.

Croats blame Serbs, Serbs blame Croats

Twenty-five years after the killing in the school in Dvor, the victims’ families still have no justice. As time has passed, key witnesses have died and no indictments are expected in the near future.

The source from the Croatian State Attorney’s Office said that the perpetrators remain unknown.

“In spite of all the actions that have been undertaken, sufficient evidence has still not been gathered to build justified suspicion against a specific perpetrator,” the source said.

The Serbian War Crimes Prosecutor’s Office gave an even briefer summary of its progress. “The Serbian War Crimes Prosecutor’s Office cannot estimate how close it is to bringing an indictment against those responsible for this crime,” said a source from the Belgrade-based prosecution.

Unsurprisingly, the Croatian State Attorney’s Office suspects that the perpetrators were Serbs, while the Serbian War Crimes Prosecutor’s Office thinks the opposite.

Strange omissions in the investigations on both sides

IRD has identified strange omissions in the investigations. Crucial commanders in Serbia have not been interrogated by the Serbian War Crimes Prosecutor’s Office.

Danish investigators Willy Hove and Villy Bøgelund who were at the scene of the school massacre only a couple of days afterwards collecting evidence for the ICTY, were also not questioned by Serbian or Croatian prosecutors.

There are further unclear points in the whole case. What is the link, if there is any, between the killing of the Ivelics and the massacre in the school? Do the Danish soldiers speak the truth when they claim that before the massacre, several people were led out of the school? Could one of them be the young man whose corpse Baburak discovered?

Concerning this topic, Croatian State Attorney’s Office disputes the claims of Danish soldiers.

“The statements of the Danish battalion members about some people being led out of the school are till now not confirmed by the statements of other persons, nor could it be concluded from the other gathered information, although in the process of criminal investigation these claims were examined as well,” said the source from the attorney’s office.

Furthermore, why is Croatian State Attorney’s Office speaking about 10 victims of the massacre, while the Directorate for the Imprisoned and Missing People – an institution related to the Ministry of War Veterans – counts only nine?

Finally, it is important to note that there were other Croatian and Serbian units present in or near Dvor, with whose commanders IRD’s investigative team was not able to talk.

One of the units is the Croatian 262nd Special Reconnaissance unit. Their commander Matija Cipric is a native of a Zamlaca village, less than three kilometers from Dvor. Serbian NGO “Veritas” accused Cipric that his unit committed the attack on the school, but without any real evidence.

Cipric died in early 2019 and IRD was not able to speak with him. In the 2012 interview for Zagreb daily Večernji list, Cipric most determinedly rejected claims that his soldiers could be involved in the massacre.

“I am disgusted by this crime. To kill a civilian, and an invalid besides that – only a human scum could do this. My ethics would not allow it. Neither myself nor any of my soldiers did it”, said Ciprić.

According to him his unit retreated from Dvor on 8th of August before the crime, and he guaranteed that none of his soldiers was near the school at the moment of the massacre . According to the IRD’s knowledge, Cipric was interrogated several times by the Croatian State Attorney’s Office.

As the crime was committed in Croatia, the authorities there should be primarily responsible for delivering justice. Yet, Croatian judiciary in general proved unwilling or unable to prosecute war crimes committed against the Serbs. Although the exact number of civilians killed during the “Operation Storm” is disputed, there are at least several hundred who died.

The Croatian State Attorney’s Office has evidence of 33 war crimes committed during the “Operation Storm”. According to the Attorney’s office, 214 civilians were killed in these crimes. However, the Croatian Helsinki Committee for Human Rights published the list with 677 names of civilian which got killed or went missing during and after the “Operation Storm”. The true number is most probably somewhere in- between.

A quarter of a century after the military operation, Croatian judiciary has managed to process only two of the noted 33 war crimes, and even these two are not complete. One verdict is still pending and in both cases, only two perpetrators have been convicted.

Both are low-ranking members of Croatian Army.

The Croatian authorities’ attitude toward the victims of the Dvor massacre is highlighted by the fact that according to information published by media, only two of the nine (or 10) victims – Zorka Maric and Jovan Macut – have been identified by DNA analysis so they could be given proper funerals by their families.

The other victims’ identities have still not been confirmed by DNA analysis, at least according to the IRD’s information. Croatian Directorate for the Imprisoned and Missing People refused to answer IRD’s questions on this issue.

The unidentified victims should still be buried in unmarked graves in Petrinja, the cemetery’s director told IRD.

Under this grassfield in Petrinja most of the killed people form the school should be burried. With no marks at all. Photo: Jerko Bakotin.

Relatives to one of the killed Serbs go to court now

Zorka Maric’s relatives have engaged a lawyer, Sladjana Cankovic, who said she plans to file a complaint to the Croatian Constitutional Court about human rights violations caused by the ineffective investigation into the case.

“If it is rejected, we will bring the same complaint to the European Court of Human Rights. Twenty-five years after the crime was committed, nothing can justify the lack of prosecutions of the perpetrators,” Cankovic said.

“As in many other war crimes cases, especially those committed against Serbs, without the political will, the case does not make it to court.”

This story was first published in Balkan Insight. This version is extended with a lot of extra information.

Jerko Bakotin and Sasa Kosanovic are journalists from the Croatian weekly newspaper Novosti and Nils Mulvad is an investigative journalist and managing editor at Investigative Reporting Denmark. This article was enabled by BIRN’s Balkan Transitional Justice grant scheme, supported by the European Commission, and Reporters in the Field, a programme by the Robert Bosch Foundation hosted together with the media NGO n-ost.